Musty is a fashion designer from Boston, MA. I got the chance to ask him some questions about his previous collection, “The Common Man,” what he’s working on now, his inspirations, and his experience working with the Museum of Fine Arts’ “Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation” exhibit.

Where should we start? How about your name? I feel like that’s a good starting point.

No one really knows my real name, and I really enjoy that, if that makes sense. In the sense where like, Musty when I was 17 versus what it is now, and like the connotation and meaning I’ve given to it now, I enjoy the fact that no one knows my name. I’ve literally created a character, because all my work is about creating a setting or creating a character, or a narrative that, like, tells a larger story.

I don’t know if I ever told you why I call myself Musty. But, it’s because my name is very, it’s very layered; when you think of Tyrone Smith, like those are two incredibly basic names, right. They’re also just incredibly English names, in the sense where my family is from Jamaica, and you know that Jamaica only became independent, I believe in 1962. And, you know, it’s just–it’s a slave name. I decided when I was making Musty, what it is right now, where it’s going, I decided that the reason for me picking Musty specifically is to kind of–if you think of Tyrone Smith, right–the reason that those names are so basic is because in English/UK society, that is just kind of a clean name, a socially acceptable name. Those are the names that are good. So, I was like, ok–what’s a name that’s bad, that has a bad connotation, that I can just “yoink” and take it, and make it into something that’s this “aristocratic” thing that’s not for aristocrats, if that makes sense.

Yeah, totally. Like, making “Musty” the new good name.

It’s like the new good name. There’s a reason why people like Gucci, they like the name, it rolls off the tongue.

That’s true, I see that. I never really thought of it like that.

I wanna reinvent that word [Musty]. And it’s so funny, I remember, this sticks with me so heavy. One time, Anya [Musty’s girlfriend], she took a video during one of the old Musty drops, it was just like, a shirt with “Musty” on it, and in the comments, some dude was just like, “why would I buy a shirt that says ‘Musty’?”

Haha, yeah, but that’s the point!

But that’s the point!

You’re reclaiming it.

It’s like this weird paradox–I would like to think that I make good work, that I make clothes that someone out there would enjoy and wear, but at the same time, I’ve normalized Musty for myself. That’s nuts to me. This person is like, “why should I wear it,” well, there’s a plethora of reasons why you should wear it, but if you don’t wanna see those reasons, and if you don’t wanna understand, then fuck you. You can go wear Louis Vuitton.

When you say that you’ve normalized Musty, I totally feel that. When I think of Musty, I don’t even think of the real definition anymore, I just think like, that’s the homie!

That’s fire! See, that’s what I mean. It’s a mission that’s almost impossible, trying to sell a $2000 suit with a label that says “Musty.” But I feel like I’m quitting if I change the name.

You don’t think you’ll ever rebrand, it’ll always be Musty?

I feel like what I’m doing now is a rebrand. I sat down with a couple people I really trust, and I was like, level with me: should I change the name? And, you know, they all gave their opinions, but it ended up being two sides: no, you shouldn’t because I feel like you’re quitting [if you do], and, yes, from a business standpoint, that is an awful fucking name, and you will lose thousands of dollars. I love the name, and I like the concept, and it’s changed for me, and it’s working, but it’s just a slow process.

It’s polarizing. Either it’ll be accepted or it won’t, and I feel like that’s the point. You can weed people out that way.

Exactly. It’s the same reason that I collect Yohji Yamamoto. Yohji doesn’t follow any seasonal trends, meaning that he doesn’t release spring, summer, fall, winter, he just does whatever he wants to do. And he doesn’t follow any [stylistic] trends, that’s why he has his own unique silhouette. He doesn’t listen to what people are saying, he just does what he wants to do. He’s not a household name, yet, he’s one, the master of tailoring, and two, has a niche fanbase. There’s a reason that my entire closet is only him. I’m not the only person who’s into him that only has him in their closet. There’s a reason. Because he plays into a specific niche, and I want to do the same thing. I don’t want just anyone wearing my clothes. I don’t really care about that. I want this specific group of people that understand and realize and appreciate what it is that’s going on.

You want people to make a conscious decision to rock your shit. Like it’s not so widely accepted and watered down that everyone rocks it. I really respect that.

What’s your biggest inspiration when it comes to designing?

That’s a hard question because my design philosophy is to be a zeitgeist. I want to take in as much information about as many things as possible, and then translate that into my work.

We could argue that Jean-Michel Basquiat is one of my biggest inspirations.

That’s what I thought!

But that’s the thing, I would think that on a surface level, but it goes deeper than that, because when I’m making my garments, I’m listening to jazz, that’s what inspires me actively in that moment. But when I’m thinking about what the concepts are and what it is that I’m making, I’m looking at the world and I’m looking at what’s going on right now, and I’m also examining myself. I was describing this to my friend Sam as like a conversation–I figure something out, it hurts me, or it makes me feel some type of way, and then I go ahead and communicate that through my work. That’s what being an artist is.

What’s the ethos of your brand, Musty01?

I would say it’s to be a modern communicator between myself, my surroundings, and the people I interact with. Meaning like, even with the stuff I’m working on right now, or the stuff that I did last year, around December, those garments were made with a specific message in mind. People can say–a lazy answer would be that it’s [Musty] for Black people. I want to expand the intellectual property and wealth of my people.

When you mention the garments that you worked on last December, are you talking about “The Common Man”?

Yeah! But not even just that, I’m also talking about the ethos right now. But, Musty is a communication tool. When you look at Basquiat’s paintings, the first thing that comes to mind isn’t really “what is it for?,” it’s more like, “he’s speaking to me.” I don’t know what it is he’s saying, I have to decipher that for myself.

Basquiat’s works have always felt very intimate to me. They’ve always seemed deeply personal.

Exactly, and that’s where I’m going with my work.

I have these overarching messages, citiques, ideas, ideations that are more political and grounded, and I’m trying to incorporate myself in my work as well. If you look at “The Common Man,” it’s really juxtaposed by “Akane.” But I like them both. I’m into them both. They came from the same mind. If you look at “Riding With Death,” one of Basquiat’s last paintings, it looks very different from his early work, but they’re from the same mind. So, it’s the same voice. You’re still communicating, but the world around you changes. In turn, you end up creating differently so the world can understand that communication. And I think that’s where it lies, I want my garments to be looked at as pieces of art. And I want them to be these high pieces of art that people where I come from understand. It’s palpable to those people. But that rich white person that’s running the MFA [Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, MA] also understands it.

I like that concept of a very broad communicator that takes in different inspirations and puts out what it is that needs to be conveyed. I think that’s really interesting. At the end of the day, that’s what we are as people.

Exactly. We speak what it is that we want to speak and hope that someone listens. I think that being an artist is a never ending cry. I think that for me to develop as a person, I couldn’t do what I do under the name “Tyrone.”

When I go to work, or when I am speaking to somebody in a position where I am the “lesser” being, I allow myself to be called Tyrone, if that makes sense. Because that’s not me, that situation is not me. That situational identity is not me. I’m kind of playing this character of Tyrone in that moment.

When I’m making my work, that name just doesn’t feel right. It doesn’t fit.

Your true self is Musty. It’s who you’ve chosen to be, it’s not what’s been imposed upon you.

Right! I feel like I can make the most truthful work that I can make under Musty.

Who would you say your top 5 favorite designers are?

Yohji Yamamoto, Maison Margiela, Raf Simons, I’m really starting to get into this guy, Yang Li, he’s really cool, he has a lot of stuff going on right now, Xander Zhou, his garments are amazing.

How would you describe Zhou’s stuff?

Alien. Alien. He’s like Rick Owens, but he’s not. I don’t like to compare too much. He’s in his own lane. He’s one of those designers that kind of minds his business, he’s had his hands in a lot of things, I know that A$AP Mob was a big fan of his for a while and they wore a lot of his garments. But he’s still kind of unknown, and he definitely deserves more recognition. I also like Robyn Lynch. Yeah!

Can you tell me a little about your experience working with the MFA’s Basquiat In Context/Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation exhibit? HAHA! Are you legally allowed to?

HAHAH! What? Yeah! Of course! The show would’ve happened already if it wasn’t for coronavirus.

Working with them, it was amazing. I got the opportunity because my childhood best friend’s mother, either her sister or close friend, is a curator at the MFA. I was talking with her about Basquiat, and she was really wowed by my knowledge. I was also talking with her about “The Common Man,” and she loved it. It was received very well, and she ended up getting in contact with her friend, Makeeba at the MFA. We ended up going to a roundtable discussion about what they were going to do for the show, suggestions for how it could be well-received, those kinds of things. At first, I was really nervous. But, I ended up saying something about [Black] youth, and making sure that the exhibit isn’t just for white women. I work at a museum, museums are white women territory. It makes me sad to see that we’re [the MFA] smack dab in the middle of Roxbury, Mission Hill’s right there, and hardly anyone [in those areas] goes to the MFA. I think that as a child, the only times that I went to the MFA, and I’m from the city, were for school trips, and I didn’t care. This [the Basquiat exhibit] is the perfect time to get kids that aren’t molded into the stereotype of being Black in America yet, and get them into art, get them into reading, and having them realize that these things can be cool. It doesn’t matter if they’re cool or not, I love listening to jazz, what, it doesn’t have lyrics, so what? I love to read books. It’s cool to learn, and I want kids to understand that, because when I was growing up, I didn’t understand that, and I was a smart kid. I got off lucky. But then you have these kids that just don’t care, it’s sad. The show was something that I saw as an opportunity to be accessible, and it was so cool.

I had never seen a Basquiat in person. We went to a private walkthrough of the gallery, when they were still putting up a lot of stuff. There were a couple Basquiats up. There was a leather jacket that he made. Like I said, he was communicating something. And the energy, the energy you could feel in the room with his works, and Rammellzee’s and Fab 5 Freddy’s. I enjoyed that the exhibit didn’t just showcase Basquiat, it showcased his peers, Basquiat worked with everybody. They were just as good. I understand their works just as well. You could get the energy of New York in the 1980s and everyone just making work together and no one caring about clout or Instagram or Twitter, or bullshit. People just made.

I totally agree with you in the sense that an artist often is not only one singular person, I think so many artists really rely on their peers for inspiration, collaboration, etc, and I think it’s important to highlight that side of the story.

That brings us to my next question perfectly, what do you think of Boston in terms of its arts community. Would you say it’s like 80s New York City?

No, I didn’t even have to think about that. No.

I think that Boston was right at the cusp of a Renaissance right before quarantine started. My reason behind that thinking was that everyone [artists] was starting to do stuff in groups, not necessarily together yet. The thing that was stopping us [Bostonians] was creating together. If you look at Keith Haring’s works, you best believe that he was hanging out with Basquiat at night, and Basquiat was hanging out with Andy Warhol, and Andy Warhol was hanging out with this person, you know what I mean? And they didn’t care, like Basquiat was a famous painter, but he was still living in Manhattan, hanging out with people that no one knew, no one really cared about [artistically], he was just doing things. Basquiat was literally everywhere, how is he doing all these things in New York, and ends up in the Comme des Garcons show as a runway model? A painter. Painter. He was around.

If you think about “Downtown 81,” a short film that he was featured in, he’s the most famous person in that film, but he doesn’t care. I think the problem with Boston is that people only care about one thing [clout], and they don’t care about making things together. For me, it’s a really lonely environment. If you’re not working with your peers, you can’t elevate. Period. You just can’t go as far with your work. There’s only one mind. The thing that was beautiful about Basquiat’s and a lot of artists that I enjoy’s works is that they’re interactive. These people were around other artists. When I was at the MFA show, there was this Keith Haring piece showcased, it was this beautiful neon column, he made it with his assistant. His assistant and him would just collaborate on works. He didn’t care about status. Nobody cared. They had this fridge at the exhibit, Keith Haring had written on it, Basquiat had written on it, all these famous artists wrote on it, but it was also this fridge that they had put in the middle of their shitty studio in Manhattan, and people had just drawn, and written all over it, random people. Nobody cared. That can’t happen now. People won’t do that now.

Clout is toxic. It kills me. When I was 17 I couldn’t take it; at that time, Musty was a very different thing, I had “clout,” everyone in the city knew who I was, they enjoyed my work. But for the wrong reasons. And I’m sure it’s the same reason that led to Basquiat’s overdose. At a certain point, people weren’t hanging out with him for the right reasons anymore. People stole his paintings when he left them places. They would steal them and sell them. That’s the energy Boston has. Say I make it, say Musty receives the exact reaction that I want it to, right. I’ll have people that have been forsaking me for years asking for things. Feeling like they’re entitled to certain pieces of the pie. It’s the reason that no one can elevate.

The city has so much potential. But people are caught up in the wrong things. People don’t want to make things. People want the latest Off-Whites, they don’t want to make them. People don’t wanna make the next Rick Owens, they want to buy it. So that they can flex. It’s corny.

I feel like Musty will never be accepted in Boston as much as I’d like it to be.

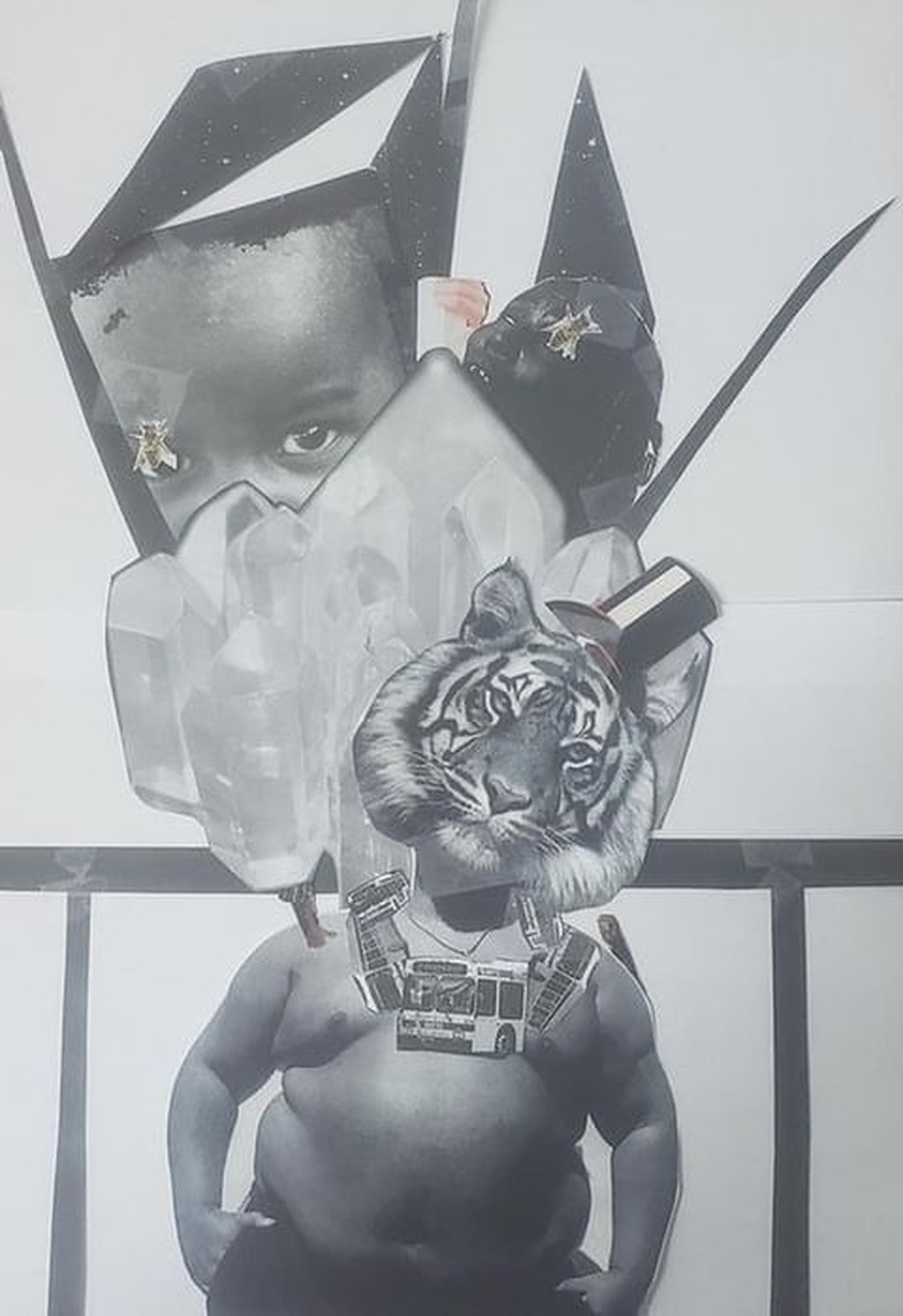

What was the inspiration behind creating “The Common Man”? How would you describe the process?

As a preface, I’d say that “The Common Man” really changed my life. It changed my view. So many factors went into inspiring it. I would say what started it was the death of a loved one. I think deeply about everything, but I had never really thought deeply about death. I started to think, “what if I died right now?,” I would look in my mirror and think that. I couldn’t function. I decided to take a semester to process all of these feelings. My mind shifted from “what if I died right now” to my quality of life as a Black man. It seems like my quality of life is less than a lot of other people’s quality of life. That’s not fair. All because my skin color? That’s not fair.

I started looking into the history of slavery, and how it started in the United States. I read Howard Zinn’s The People’s History of the United States a bunch of times. I was so taken aback and hurt, I started to see my people in the city, on busses, trains, and I’d feel more hurt than I ever felt, once I got off the train, I’d cry. It’s not fair, and we’ve had to just live with this, and deal with it. Look at the lynching of Ahmaud Arbery. It happens everyday. My people are dying. How am I afraid of death, and my people are dying? I couldn’t do it. I needed to process it.

I decided to poke fun at the aristocracy, the people who created the slave system. I didn’t only look at the United States, I also looked at Jamaica, where my family is from. My grandmother is a Maroon, essentially an escaped slave who ran into the mountains, where the Englishmen couldn’t find them. I have this rich backstory, and I’m blessed to know it. So many people don’t know it. That hurt me.

I made garments that made fun of the aristocracy; that’s why I made these voluminous pants. I wanted to make “the slave” [the model] loud in their garment. When you take a person from a specific country and you bring them here, and you push your ideas upon them, about aristocracy class–I’m specifically referring to the house slave–when you push that onto them, it can be a terrifying experience. It’s a terrifying experience to feel like your values are inept. So, I wanted to poke fun at that. It was my first set of garments that had a loud reception. I’m not gonna say a positive one, but a loud reception. I heard what people had to say about it. People communicated with it.

As for the process–my school asked me about that as well. I know I always bring it back to Basquiat, but there was this one interview from the 80s where he was asked where he gets the words that he writes on his canvases, the words that he writes and crosses out. And he responded that he didn’t know, that they just come to him as he paints. I can relate to that. When I was making the garments for “The Common Man,” I was just drawing; I ended up drawing the two sketches for the pieces that I made mindlessly. Then I started pattern drafting them. My professors asked me how I got the shapes that I used in my patterns. I didn’t have an answer. When I pattern drafted, the shapes just came to me. I just knew how to make them. Nobody had taught me that.

Every aspect of “The Common Man” was thought out. There’s a reason why “the slave” [the model] is my friend Awele, they’re from Africa. It’s interesting to see this diffusion of culture; they’re from Africa, I’m from Jamaica, we’re in the United States, and we’re interacting with the descendents of slaves in this region of the world. There’s also a reason why the garment that she’s wearing is made of 100% luxury cotton. The slave is taking it back. I’m making things for us. The white man can buy it, but it’s not for them. They can’t own it. They white man can buy it, but they can’t own it.

The process included a lot of research. Everytime I worked, I forced myself to watch a documentary about slavery in the United States–everytime, they seemed to get darker and darker. I stumbled across one that was from the 50s I believe, where elderly former slaves retold their experiences. It was so awful and painful. I’m holding back tears now. It’s so brutal to think that someone could do that to another human being. And in 2020, I’m being told to get over it. I’m told that my work shouldn’t be all about race.

But how can it not all be about race?

How can it not! It’s what shaped me. All the interactions in my daily life have levels to them. And you want me to get over that? I’m trying to make garments that are beautiful, that are understood. I can’t not talk about race. I feel like that’s a perfect intro into what I’m working on now.

Let’s talk about that!

I never realized how hard it is to talk about my process for previous works. I usually give my works away. When I was done with the “Akane” samples, I gave them all away. I don’t like to be surrounded by the old. I like to look toward what’s new. I even feel that way about “The Common Man.”

My new project is called “The New Regime.” It deals with government, military entities, and oppression on a systemic level; how oppression and pain manifest themselves, like how Black people feel when we walk past a cop, but captured in a garment. I want to create this other world, where there is a “Big Brother” entity, but for the oppressed. This is a regime for those that are oppressed. I’m flipping it. It’s darker, sleeker, more sartorial wear. I’m not following seasonal trends anymore.

I’m really excited for it. Thank you so much, dude. I really appreciate you taking the time to talk with me. Any love that you want to spread?

Shoutout to anybody who reads this, my goodness, it’s gonna be a book.

Follow Musty01:

Leave a comment